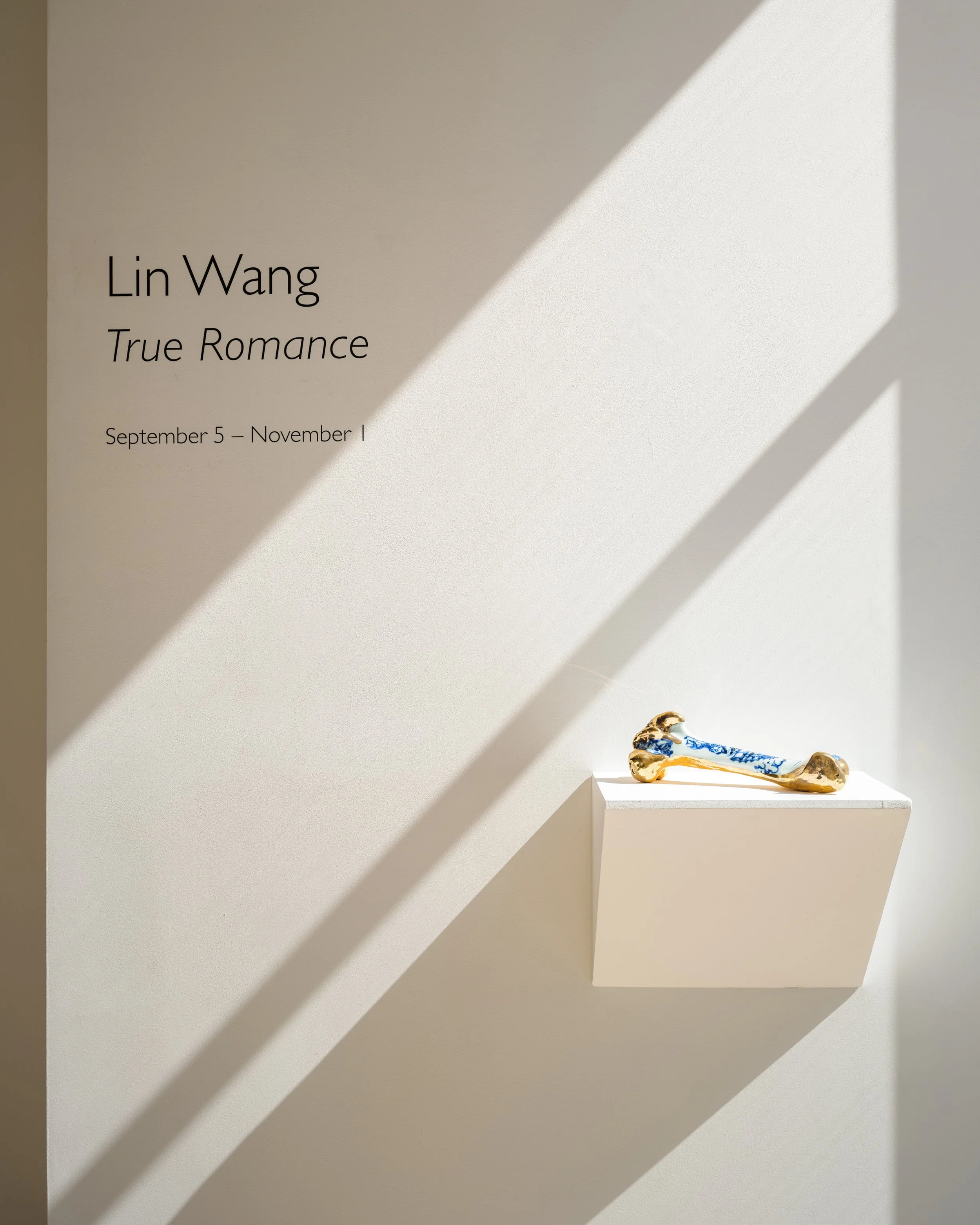

Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings project -The silk Roads

Solo Exhibition

Kunsthall Grenland, 2019 Spring

The Ingredients (Thinking Through Materials)

On Lin Wang’s Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings - The Silk Roads, exhibition at Kunsthall Grenland, 05.04 — 26.05, 2019.

Text/curator: Randi Grov Berger

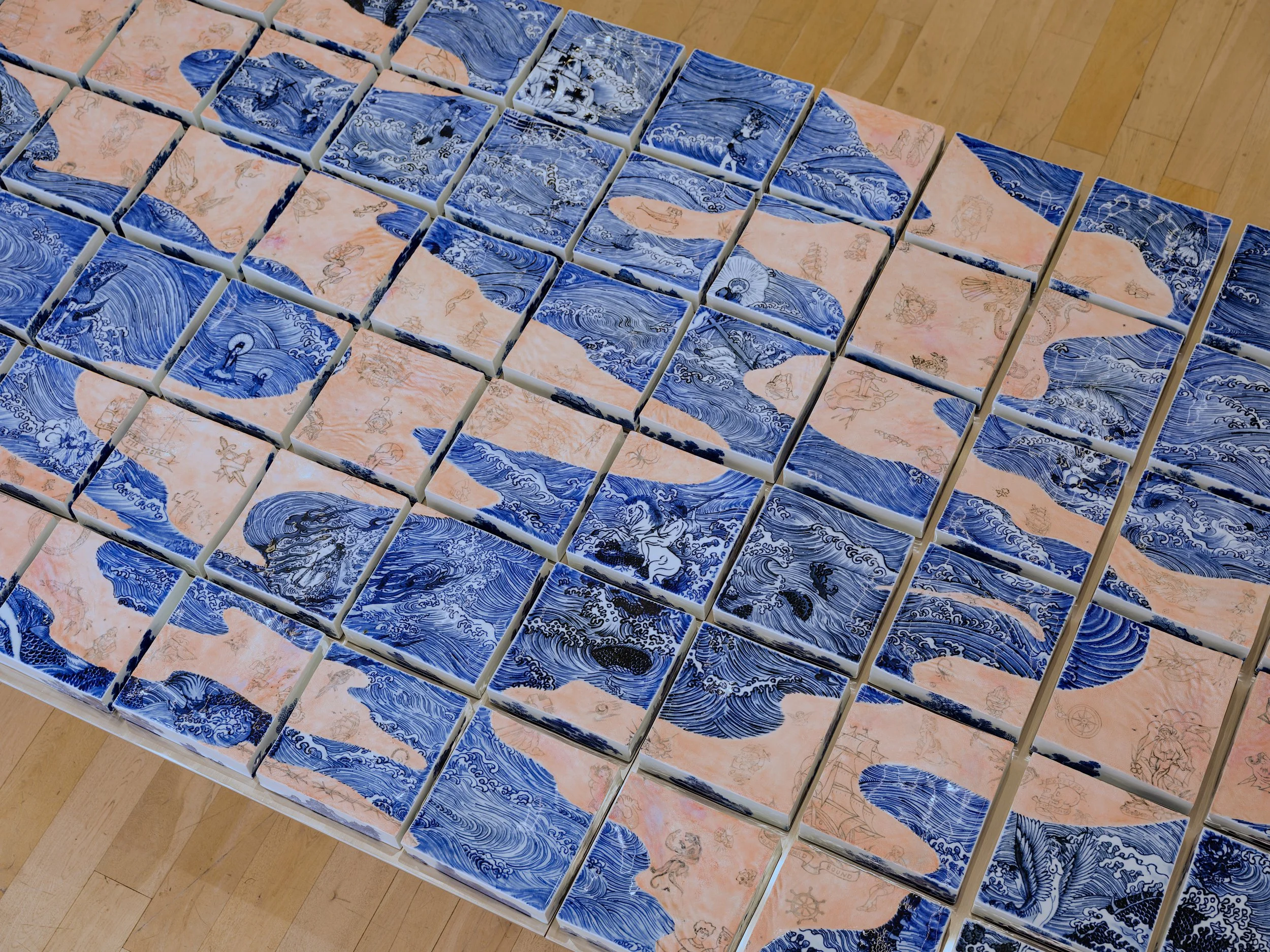

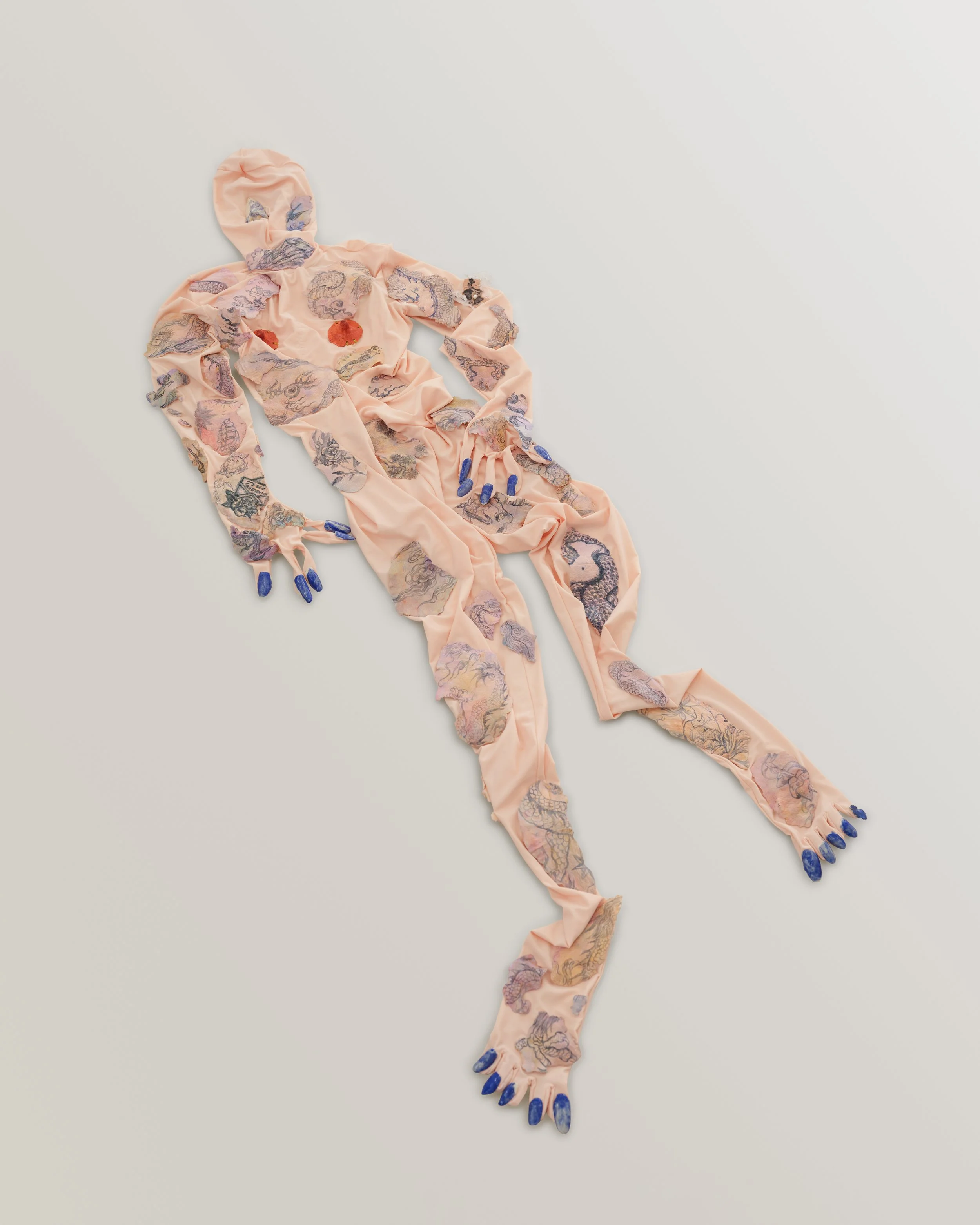

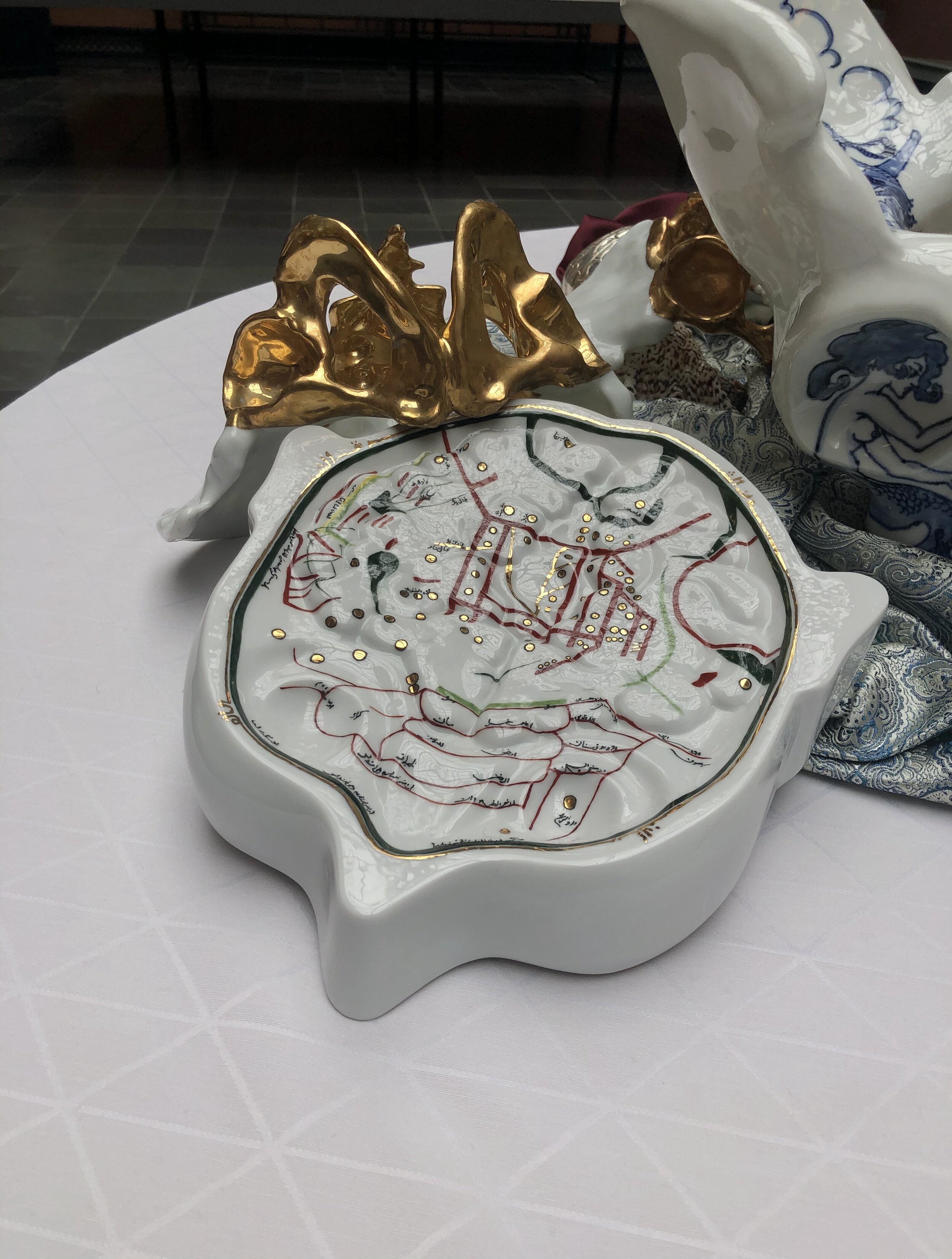

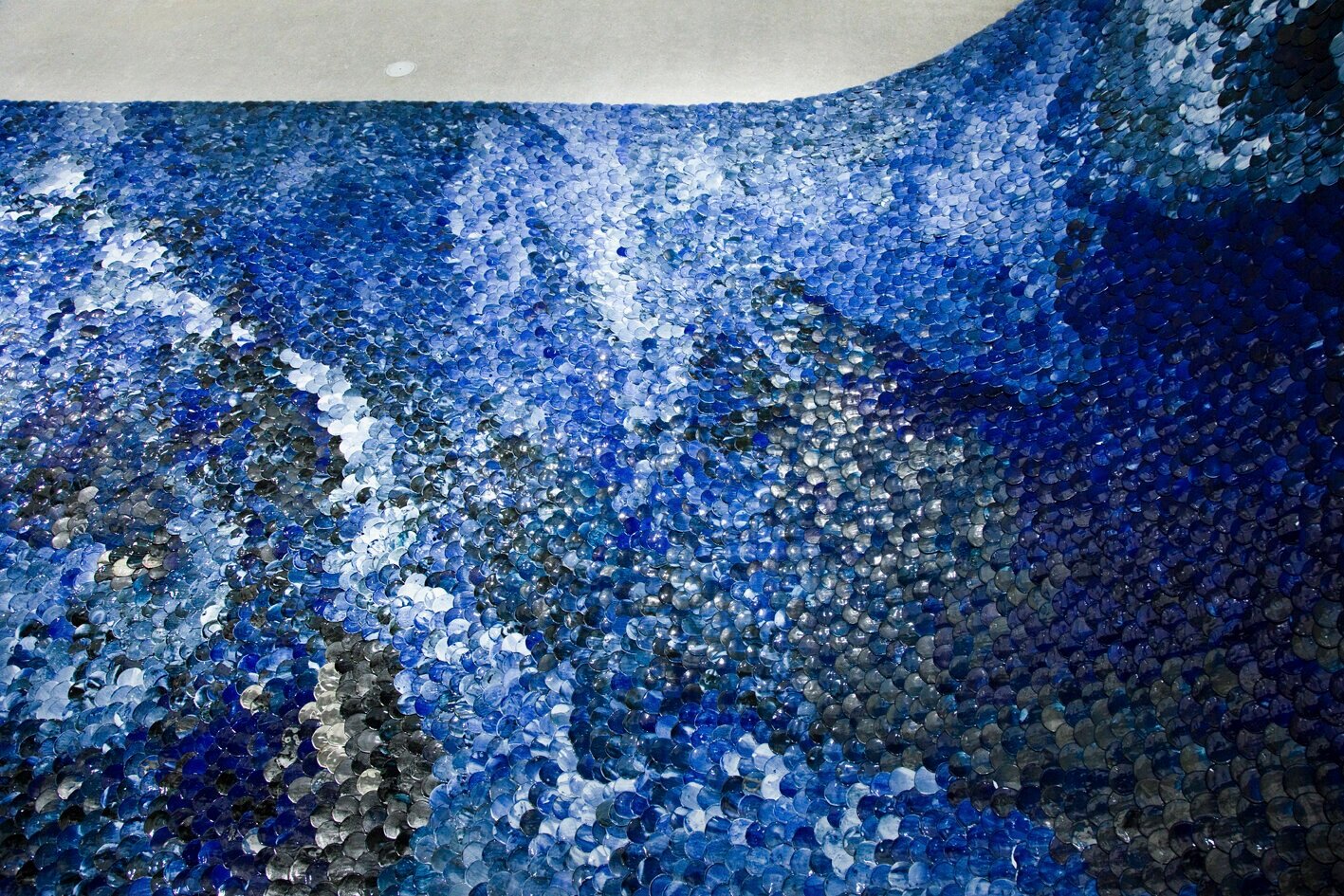

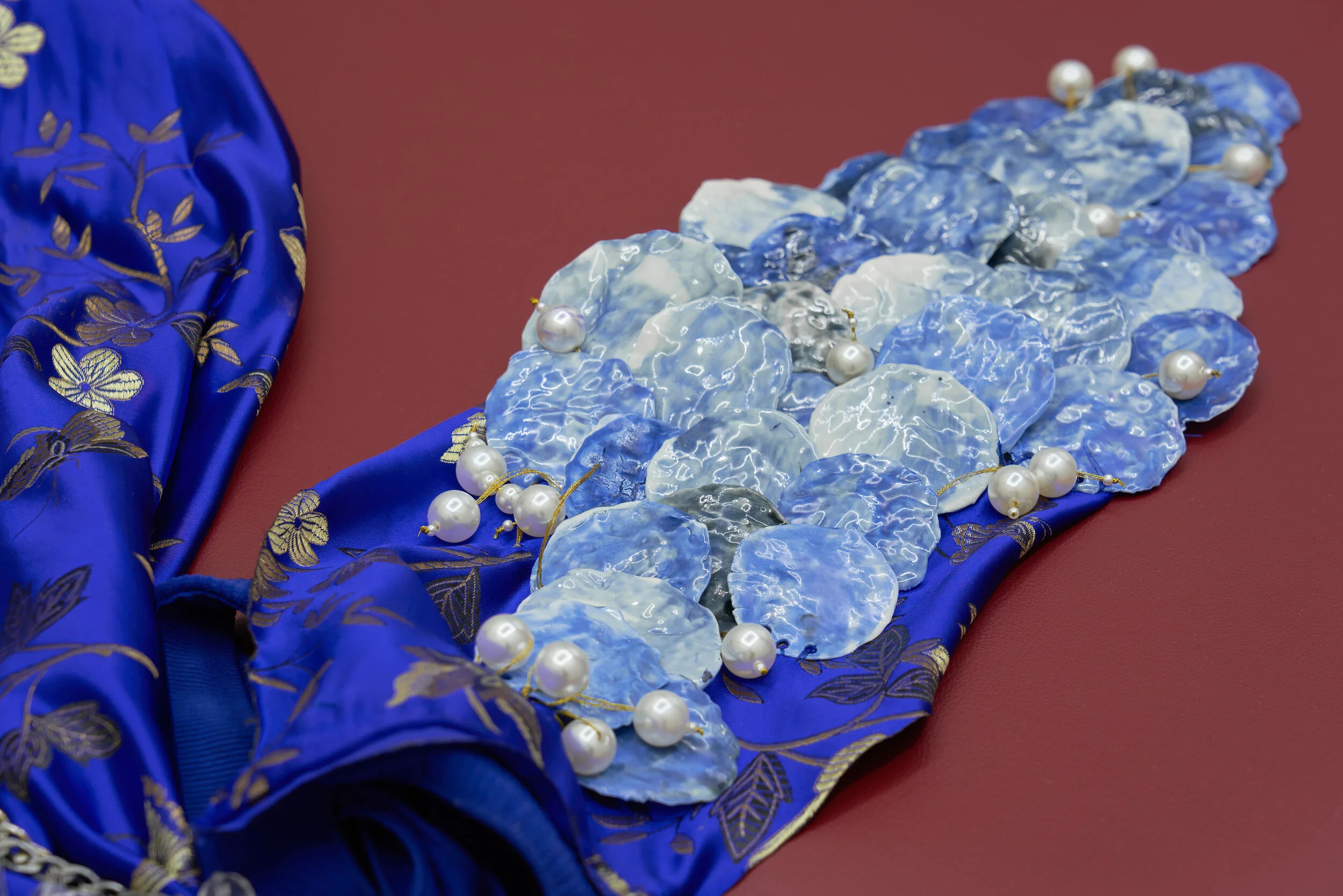

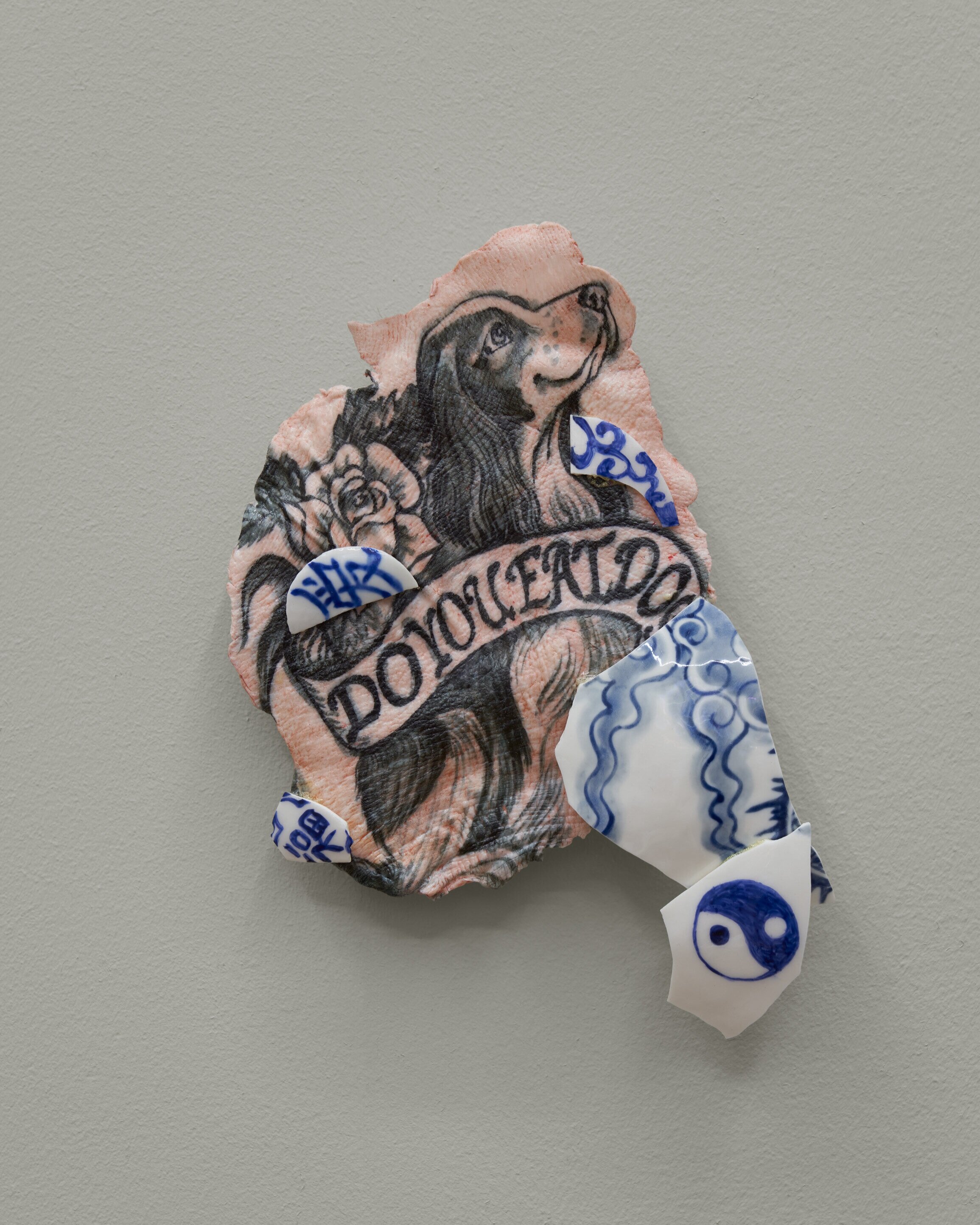

Different shades of cobalt blue is used to color the more than thirty thousand handmade porcelain pieces part of Norwegian-based, Chinese-born artist Lin Wang’s laborious installation. There is smaller object based work, where she is representing the human anatomy of spinal cord, bones, flesh, and tangent planes of the human brain richly decorated with symbols relating to her cultural background, and to traditions within the field of porcelain, as well as new Western influences (like sailor’s tattoos), and for the most part a mash-up and reinterpretation of all these, which includes some Poetic Misunderstandings. Wang is connecting similarities in our expressions, linking them through trade, like the old maritime silk roads, and on-going cultural exchange, and seeing this in connection to the on-going ambitious new Silk Roads. Exotic Dreams relates to how she as a youngster was told myths about the North, how she later moved to Norway and got face-to-face with a different reality than expected, and at the same time how she saw her country of birth anew from a distance. This exoticism of ‘the other’ is something found in all corners of the world, as we’re in a continual process of constructing our own narratives, whilst imagining, relating to and interpreting other cultures.

Lin Wang points out that the cultures we create and the beliefs we project on others - are in a continual back and forth negotiation. In her work she tries to understand China and Norway (and beyond) through her art making, and so far she has successfully used her craft to bridge cultures through creating dynamic conversations through her performances and exhibitions. Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings - The Silk Roads at Kunsthall Grenland is her largest exhibition to date, where she’s used both her studio in Jingdezhen, China, and her temporarily studio in Porsgrunn, Norway, in creating works that also becomes an assembly of different clays, glazes, and other materials (like gold) originating from around the world.

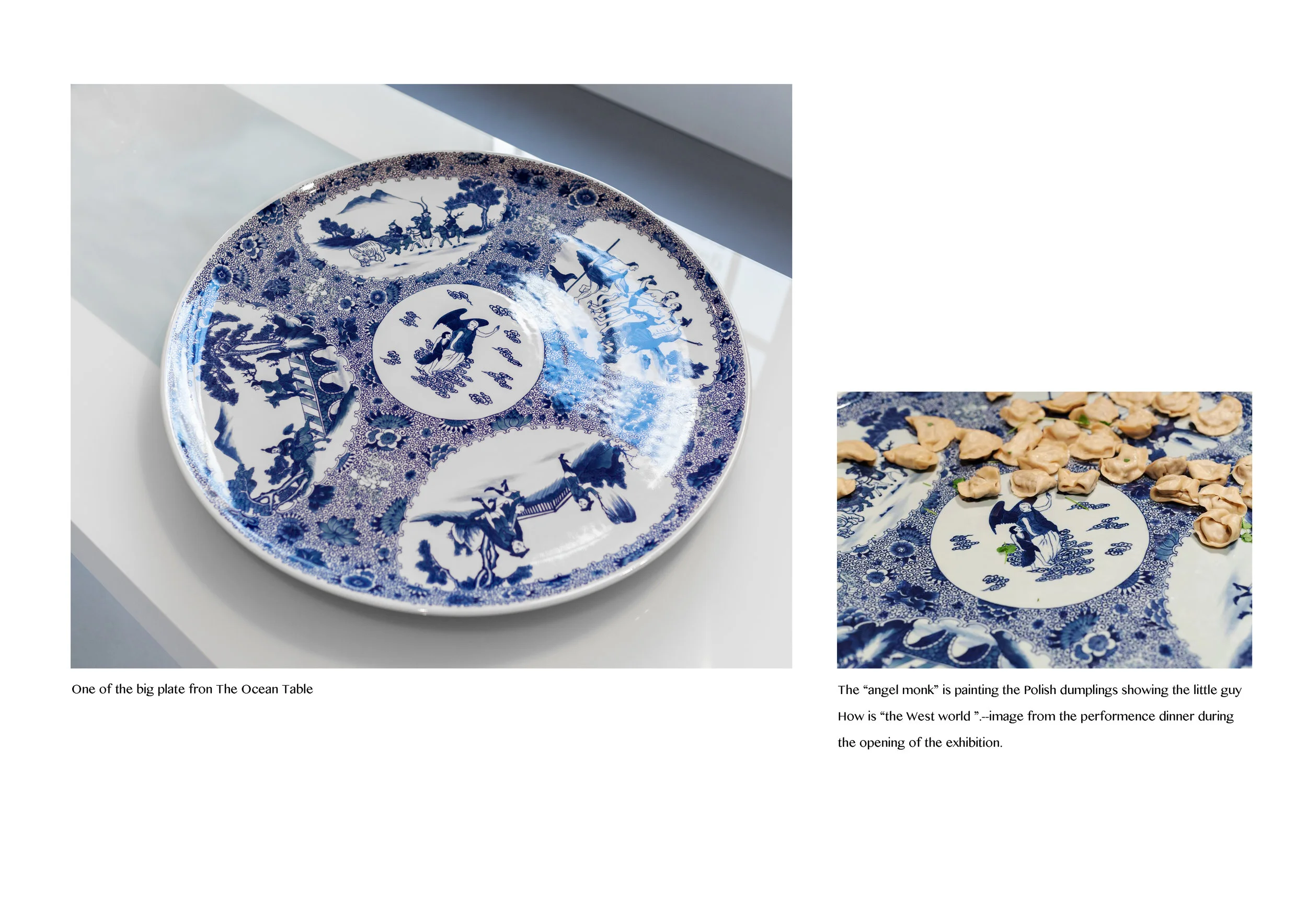

When she moved to Norway some years ago (2014) and started the master program at the art academy in Bergen, the ceramic department there was in a state of flux, being a workshop but not a separate field of study any longer. The ceramic scene itself had been through a period of changes as contemporary craft had become increasingly conceptual, and contemporary art had gone deeper and deeper into materials and craftsmanship. Wang brought a strong awareness of tradition within her field, and an enthusiasm to re-appropriate, transform and continue to develop the knowledge and character of contemporary porcelain, she found new ways to steer her ship in these rough waters, and put herself in the middle of the continually on-going theoretical contemporary craft discourse. As a visual artist using performance, conversation and installation, including extravagantly decorated dinner tables with her highly ornamented blue-and-white porcelain ware, flowers, wine, food from all corners of the world, shanty choirs performing powerful shanties from working days on-board sailing ships in the old days, and as well the art of tattooing; she speaks even more so to all our senses and touches the limbic system of our brain, giving us a direct experience of her concepts.

ELEMENTS

Kunsthall Grenland is located in Porsgrunn, which has a rich geological history that extends over a billion years. Partly the area is situated on what is called the Norwegian bedrock, which consists of granite and gneiss. Part of the center of Porsgrunn is positioned on a seabed initially formed south of the equator, which is hard to get our heads around. Here we’ll find sandstones, slate stone and limestone with rich organic content, which have laid the foundation for several industries in the area. Limestone once formed at the bottom of a tropical sea, with their beautiful ancient sea creature fossils to prove it, can now be used in cement, in plastics, paper and toothpaste.

Further north of Porsgrunn is Buskerud where cobalt laid the foundation for a lucrative industry that was in operation from 1776 to 1848 (and with reduced activity until 1898). The cobalt works (Blaafarveværket) exported up to 80% of the world's cobalt, which was sold to countries as far away as China. Cobalt was used for bleaching paper, and its blue pigments were prized for their intense color, which could be used in the glass and porcelain production because it was withstanding those really high temperatures essential in these production processes. Cobalt was once more precious than silver. When the mines closed down it was partly due to competition from synthetic ultramarine that was invented in 1826, and replaced much of the need of cobalt.

Another location to zoom into related to Wang’s installation is the Chinese village Gaoling in Jiangxi Province. Gaoling roughly translates as ‘tall hill’, and the area had a rich supply of white clay, which the word Kaolin (from Gaoling) derives from. Today the main use of the mineral kaolinite is the production of paper; its use ensures the gloss on some grades of coated paper. It’s also used in cosmetics, toothpaste, and can be used as medicine to soothe an upset stomach. It is world known as one of the main components of porcelain clay, and in the village close by, namely Jingdezhen; porcelain production originated and still flourishes today.

I find it quite absorbing to contemplate how the raw materials traceable to stars in our galaxy have moved and gradually formed the planet. How they are being extracted in most recent times, and are circulating rapidly through changing trading routes, linked to how our new habits form, and how the world economy grow and continually fluctuate. Their usage is shifting alongside human inventions, new technology and changing climate. It’s continually relevant to keep asking; where do we get them, what do we use them for and how do they fit into our economy?

COBALT BLUE

Let’s take a closer look at one of the chemical elements, which is one of the basic building blocks of the universe. This is the material that we know were mined in the mentioned cobalt works of Buskerud, and it’s as well one of the main components of Wang’s new work in the exhibition.

It actually took scientists about 300 years to lie out the Periodic Table into neat rows and columns, and in 1735 Swedish chemist Georg Brandt (1694–1768) was credited with discovering the cobalt (symbol Co and atomic number 27), as a new "semi-metal”. Cobalt is not found as a free element, but in other minerals in the Earth's crust. Brandt proved that compounds of cobalt metal were the source of the blue color used in glass, which previously had been attributed to the bismuth found with cobalt.

Cobalt ore is also a byproduct to copper and nickel, and difficult to extract, the smelting process is quite messy. Partly therefor it got named after the kobold, spirits thought to live underground. Superstitious miners believed they lured them into taking worthless ore that caused a burning sensation to those who handled them. Medieval miners blamed the sprite for the poisonous and troublesome nature of the typical arsenical ores of this metal (cobaltite and smaltite) which polluted other mined elements. Some thought the kobold creatures to be expert miners and metalworkers that could be heard constantly drilling, hammering, and shoveling. Some stories claim that the kobolds live in the rock, just as human beings live in the air.

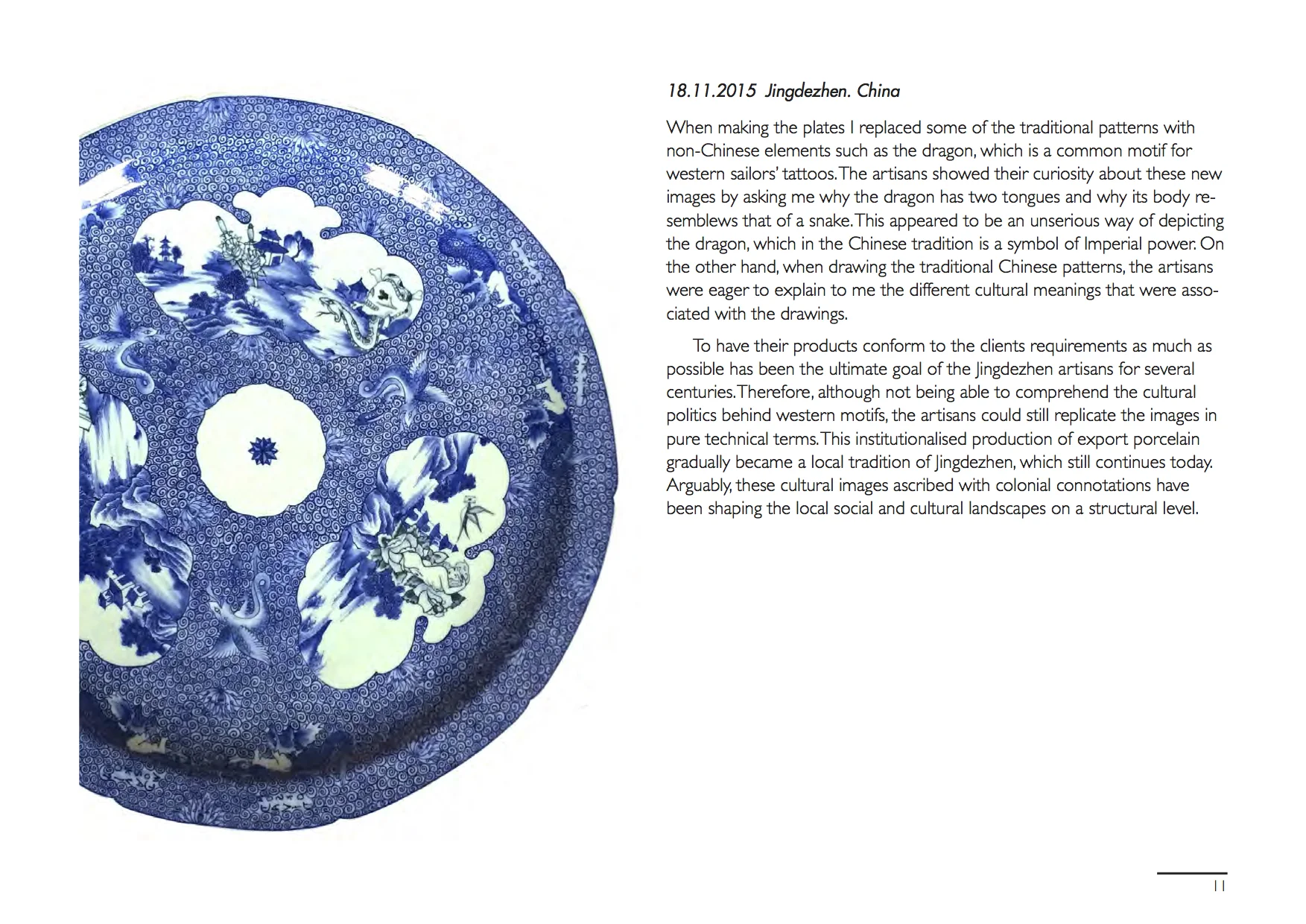

The color blue gained special significance in the history of Chinese ceramics during the Tang dynasty (618-907). In the 9th century, Chinese artisans abandoned the Han blue color they had used for centuries, and began to use cobalt blue. The cobalt ores was first imported from Persia, where it was a scarce ingredient at the time and used in only limited quantities. In the Yuan (1279-1368), Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties in particular, different types of cobalt ore and methods of application determined the distinctive feature of the shades of blue that appeared on blue-and-white porcelain ware. The plates and vases were shaped, dried, the paint applied with a brush, covered with a clear glaze, then fired at a high temperature.

WHITE GOLD

Porcelain was discovered by a lucky surprise when ancient Chinese people found some strange, exceptionally hard and solid pieces of material at their outdoor fireplaces after the fire was put out. Mixing and firing local types of earth, they started to create simple jugs and bowls. Thanks to the creative ideas and experiments during the years, porcelain became whiter and whiter. Imagining seeing porcelain with its almost glass-like appearance 2000 years ago, when we know it was made in the Eastern Han Dynasty in China. Following the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD) was the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD) and the rise in popularity in the art of tea drinking. Ceramics wares including teacups were touted all along the northern Silk Road, which ran from Xian and up along the Hexi Corridor.

Porcelain is still such a breathtaking medium to this day. The European name, porcelain in English, come from the old Italian porcellana (cowrie shell) because of its resemblance to the surface of the shell. Porcelain is also referred to as china or fine china in some English-speaking countries. Beginning in the 14th century, porcelain was exported in large quantity to Europe where it inspired a whole style of art, called Chinoiserie. By the early sixteenth century - after Portugal established trade routes to the Far East and began commercial trade with Asia - Chinese potters began to produce objects specifically for export to the West, and porcelains began to arrive in some quantity.

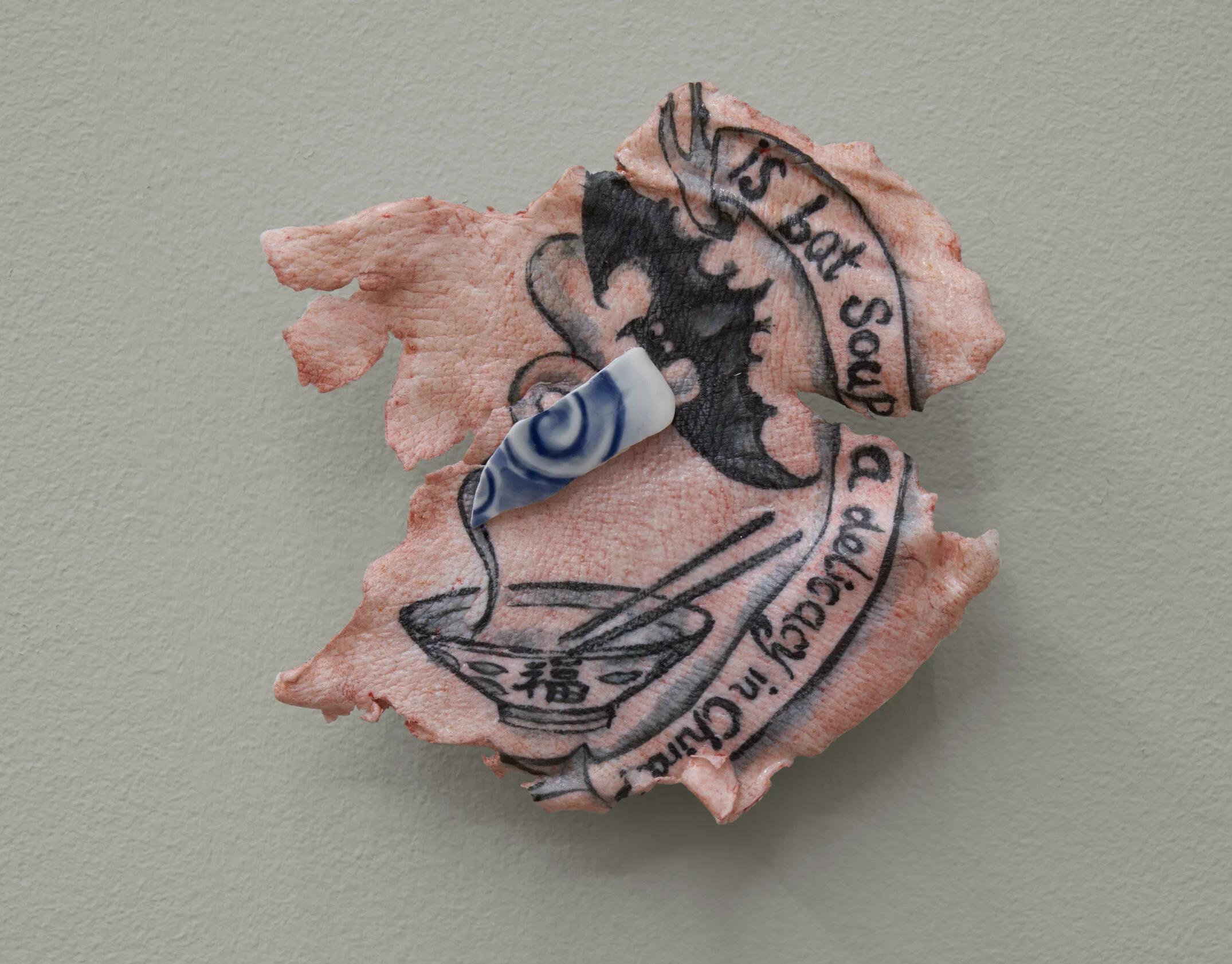

As the export trade increased, so did the demand from Europe for familiar, utilitarian forms, such as mugs, ewers, and candlesticks. These forms were unknown in China, so models were sent to the Chinese potteries to be copied. Its production and exportation facilitated a form of cultural transaction between Far East and Europe. This cultural exchange based on the appropriation of physical models and selected Chinese patterns took place in such a way that the exported items embodied the Europeans’ reading of China’s ‘exoticness’ rather than creating cultural and social insight. An unusually early example of export porcelain is a water jug decorated with the royal arms of Portugal; the arms are painted upside down, however—a reflection of the unfamiliarity of the Chinese with the symbols and customs of their new trading partner.

The Dutch had a lively trade with China and in the 17th century it imported millions of pieces of Chinese porcelain. With the Jingdezhen porcelain as a model, Dutch ceramic artists created their own unique ceramics. During the 17th and 18th centuries the Dutch Delftware ceramics became known worldwide and promoted as a typical Dutch product. However, the first Delft Blue ceramics were an ordinary copy of the traditional blue and white porcelain crafted in Jingdezhen. Delft Blue was not made from typical porcelain clay, but from clay that was coated with a tin glaze after it was fired. Delft Blue achieved unrivaled popularity, and at its peak, there were 33 factories in Delft. Of these, the only one remaining is Royal Delft, which us still in production.

With the appearance of many porcelain factories in Europe, the demand for Chinese export porcelain began to diminish, and by the second half of the century the trade was in serious decline. The porcelain industry also found its way to Porsgrunn, where Porsgrunn Porselænsfabrikk was established in 1885. The river Ælva and exsisting shipping provided good opportunities for bringing home raw materials and shedding finished products. The ingredients quartz and feldspar was found close by, and kaolin and coal could be brought on ships, with these components they could make their own blend. In the 18th century, porcelain had been an extremely luxurious product in Europe. Social reforms and a higher standard of living during the 19th century meant that demand for porcelain increased sharply. Porsgrunn was favorable for shipping to a large and growing market in Norway and Sweden, and soon got famous for their quality and design, such as the blue and white straw patterened tableware set.

Having the secret was one thing, but making porcelain was never easy. It’s still a difficult process where so many things need to be perfected before you can even get started. It’s hard to imagine when holding a porcelain object the long journey the material has been through getting to this end. There is the material extract, perfection of the blend between components like kaolin and water. Then the mold making, made about 20% larger then the finished design, the finishing touches after first firing, and customized glazes and colors, patterns, then the scary part of the “make it or brake it” last firing at up to 1400 °C degrees, which can led to either cracks or perfection. When perfectly finished, the properties associated with porcelain include low permeability and elasticity; considerable strength, hardness, toughness, whiteness, translucency and resonance; and a high resistance to chemical attack and thermal shock.

CRAFTING CONVERSATIONS

Today most of the production of porcelain making in Norway is flagged out. At most, Porsgrunds Porselænsfabrik had more than 500 employees and the factory was one of the district's largest and most important companies right up to the 1990s. Still some porcelain is produced in Porsgrunn, and the "straw pattern" in cobalt blue is still painted by the local specialists by hand. But just like Blaafarveværket these productions sites are turning increasingly into museums and tourist attractions, making the service industry their new business.

What is worrisome as most of the production of the things we own happen elsewhere, is that we live in a time where we are losing touch with the materials we surround ourselves with in everyday life, like teacups, clothes, or even smartphones. We don’t know where the materials come from; who made them and the time it took to get them to us. To get back to cobalt again, the metal have unique magnetic properties, making it essential in modern technology. We can read about how China has increasingly a stranglehold over its supply with their large investments in infrastructure in Africa, part of the one belt, new initiative project. This is now also (a quick Google search tells us) a material associated with conflict, child labor and unethical production, like so many other raw materials are. Currently there are a team of researchers working on mapping critical minerals in Europe, to see where they appear and if there is a potential to extract them, so we can not exclude the possibility that perhaps there will be cobalt (and other minerals) mining industries in Norway again in the future for new purposes.

Lin Wang, like many craft based artists, offers a contrast to the mass produced object. The past months she has shared her time between her studios in Porsgrunn and Jingdezhen. She’s been involved at the Porsgrunn Porcelain Fabric, both in her own temporarily studio there and as a workshop leader, including holding blue glaze experiments with the fabrics employers. The tools and processes are still very much the same, but it’s it still relevant to make porcelain objects today with a new perspective, and as a form for cultural building, critical thinking, and opening up for conversation and new sensations. We have the technology to 3d print objects, but the hand made have a relevance that goes beyond the industrial. The project Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings- The Silk Roads is part of a continuing investigative long-time project that she is determined to continue over the next years. By involving different practitioners from other fields in discourses on seeing and knowing -influenced by our condition of colonialism and globalization – she is maintaining porcelains relevance. She invites audiences to unsettle their assumptions and conventional understandings of history, society, and culture, as she by situating her work in the long genealogy of global trade brings to the front examples of cultural exchange where authenticity has gone lost in time.

By using the history of our past as a mirror in understanding our contemporary life and by using porcelain as a means, Lin Wang’s journey connects the past and the present, as she speaks about the curiosity and imagination of “the other side of the world” as universal to human beings in both ancient and modern times.

In Lin Wang’s installations and performance dinners, you might find yourself eating from tableware with motifs that by the first apperance seems like Chinese paterns, but which are based on motifs established through the Delftware porcelain in the Netherlands, and these again were imitations of Chinese originals, in a forth-and-back interpretation.